In Kenya’s Western Highlands around the towns of Eldoret and Iten, young runners chase dreams of glory around dusty tracks and along rutted red-clay roads, often matching strides with Olympic heroes. But when those heroes disappear around the next bend, and all that remains is the sound of their own ragged breathing, a stark choice emerges—stay on the straight and narrow, or deviate to the dark side.

⸻

Such dilemmas echo a century-old struggle in sport, caught in a moral tug-of-war between an ideal and the real.

There’s a righteous, pox-on-their-house anger rising throughout the sport again as the Athletes Integrity Unit (AIU) announced its ban of women’s marathon world record holder, Ruth Chepngetich, at three years on October 23, 2025.

Enough! We have had enough! Burn it all down, root and branch, come the cries from far and wide as yet another high-profile Kenyan athlete falls in disgrace, dragging the sport down with them.

And who can blame the indignation?

But a closer look suggests that this crisis isn’t just about right and wrong—it’s about cost, and the gulf between those who can afford purity and those who can’t.

This is the story of the moral tightrope walked when the reward for winning is not a trophy, but the survival of your family.

⸻

From Virtue to Survival

In the Victorian era, sport belonged to the leisure class—men with time and means to cultivate physical virtue.

The Cold War years turned competition into proxy warfare, as the laboratories of Moscow and East Berlin engineered human performance in pursuit of ideological supremacy.

Today, the drama plays out in small highland towns and villages where running is not pastime but lifeline.

As Bertolt Brecht wrote in The Threepenny Opera:

“First feed the face, then tell me right from wrong.”

⸻

The Numbers Behind the Names

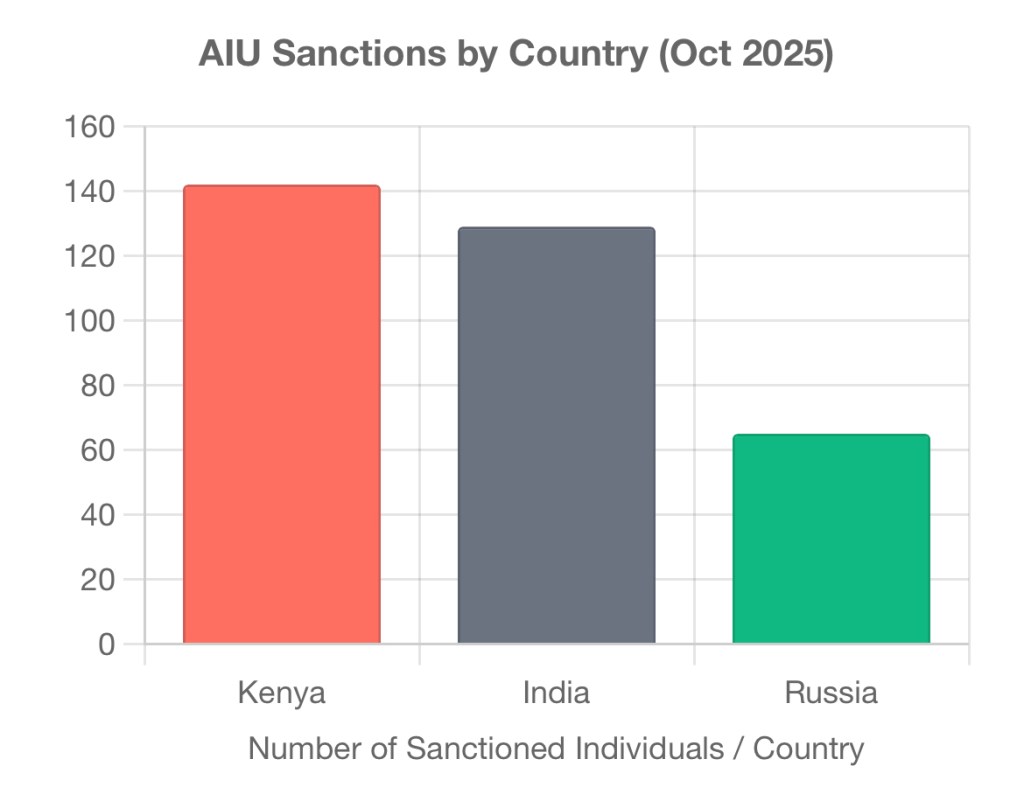

As of October 2025, the Athletics Integrity Unit’s global list of ineligible athletes stands at 675 names. Kenya leads with 141, followed closely by India at 129.

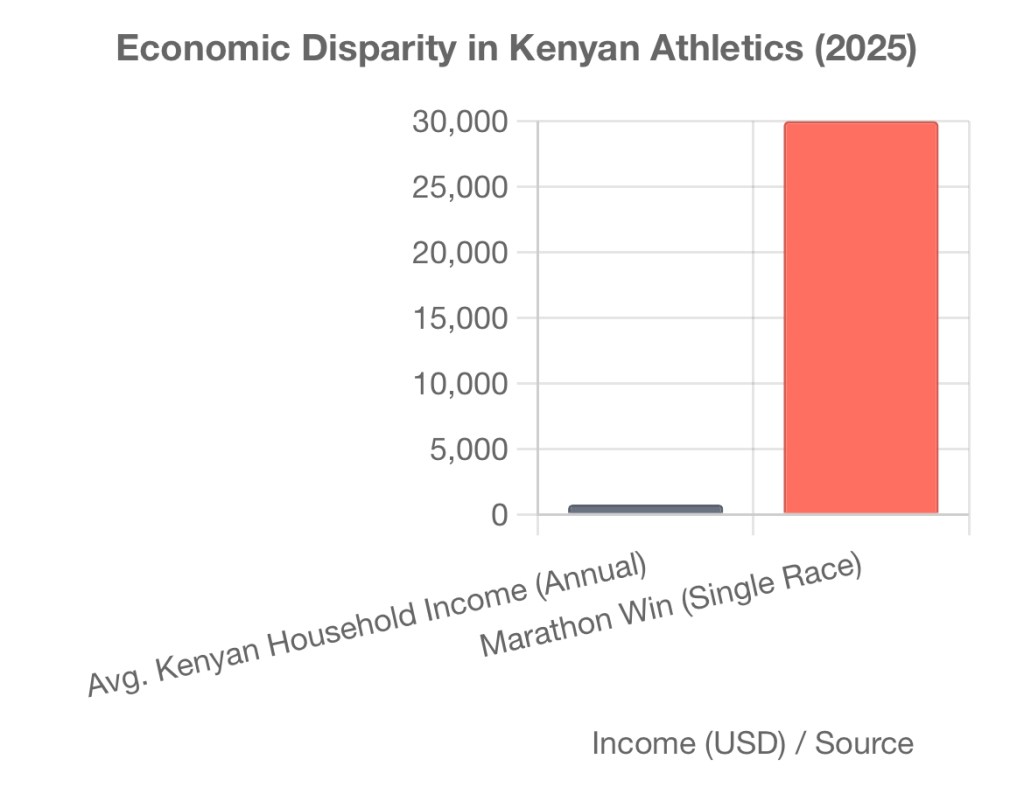

Not all of these athletes are villains. Many come from subsistence farms where an annual household income might reach $500 to $900—if the rains are kind.

A local race purse of 100,000 to 300,000 Kenyan shillings (about $750 to $2,200) equals one to three years of family earnings. A $30,000 marathon victory can transform a life.

When German Silva won the New York City Marathon in 1994, he brought electricity to his home village in Veracruz, Mexico. No American victory in any marathon represents that level of transformation.

In that light, the gap between 2:09 and 2:05 in the marathon isn’t just four minutes. It’s the space between resignation and emancipation.

⸻

A Question of Context

For runners from the highlands of Kenya or Ethiopia, the marathon is not an extracurricular activity—it’s an industry of survival. Think boxing in Mexico or baseball in the Dominican Republic.

A career can begin with a pair of borrowed shoes and end, if fortune turns, with a house, school fees for the children, and economic security for generations.

The moral calculus becomes complicated when the price of compliance is food security. In that marketplace, a banned substance can look less like a shortcut and more like a chance to keep pace in an unequal world.

Western institutions, armed with labs, lawyers, and technology, can afford compliance; athletes chasing opportunity from the margins often cannot.

That doesn’t excuse doping—it explains its roots.

The system itself is uneven. Testing, funding, and education about banned substances are often weakest in the very places producing the most talent. When desperation meets opportunity, infractions multiply.

⸻

Falls from Grace

Ruth Chepngetich’s story crystallizes this pressure.

On October 23, 2025, the AIU banned the women’s marathon world record holder (2:09:56, Chicago 2024) for three years after her March 14, 2025 urine sample showed 3,800 nanograms per milliliter of hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ)—190 times the WADA threshold, often used to mask other substances.

Initially denying any use, she later claimed she had taken her housemaid’s medication when both exhibited similar symptoms—a story the AIU called “hardly credible.”

Discovering WhatsApp messages referencing testosterone and anavar during their investigation caused the AIU to extend her sanction from two to three years, with further probes ongoing. Her marathon record still stands, but its legitimacy remains under scrutiny.

2:09:56, a record others must now chase—a mark achieved under the shadow of a systemic ban—is the perfect symbol of the crisis: a historical lie that cannot be summarily erased, nor likely topped without resorting to the same temptation Chepngetich gave into, further stripping the sport of legitimate advancement.

But Ruth Chepngetich wasn’t an impoverished hopeful. She was a global star with major victories, fees, and sponsorships. Why risk it?

The answer lies not in hunger but in fear—fear of losing what she’d already earned.

Fear of losing is every bit as powerful a motivation—if not greater—than the desire to win. Contracts, along with family and national expectations, create additional pressure to preserve status atop a narrow pyramid peak that favors the very few.

Her fall echoes a precedent: Ben Johnson’s 1988 Olympic scandal in Seoul, where his confession—“everyone else was doing it”—revealed a culture where success itself became a trap.

A decade ago, Rita Jeptoo’s 2014 EPO ban shook Kenyan running. The Boston and Chicago champion lost titles and $500,000 in AWMM bonuses, exposing a shadow economy of clinics and opportunists.

Her coach lamented, “I can’t watch her 24/7,” as Kenya’s doping stigma deepened.

The Effects of Doping on Athlete Earnings

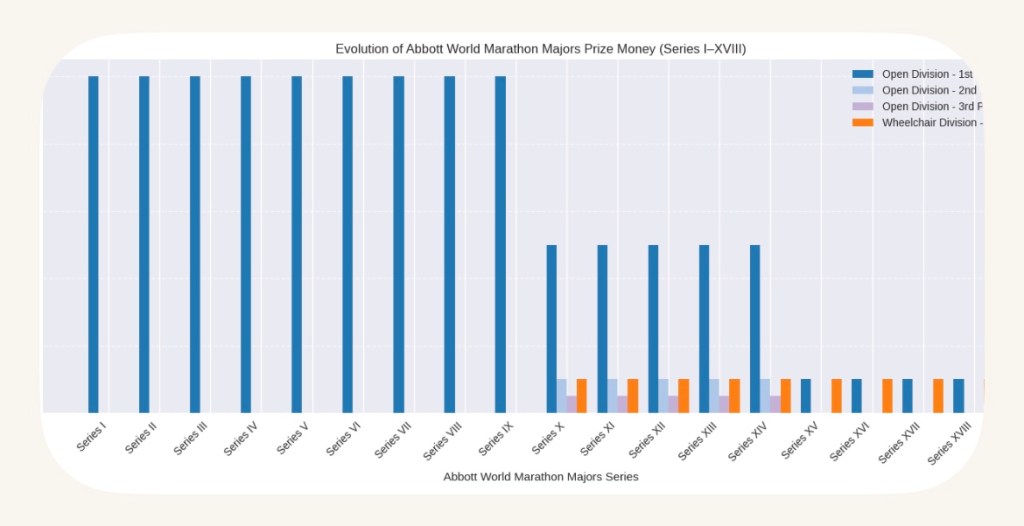

When the original five Abbott World Marathon Majors (AWMM) began in 2006, they awarded $500,000 to series winners, and continued from Series I to IX. But then, they reduced the prize to $250,000 in Series X, 2015–2016) before cutting it to $50,000 for Series XIV, 2021–2022, while adding a $50,000 Wheelchair division to foster inclusivity.

Launched to elevate running as a professional sport, AWMM’s 90% prize cut—while other pro sports’ payoffs skyrocket—was likely a response to reputational damage from doping. Scandals like Russia’s Liliya Shobukhova, Series IV and V champion, Kenya’s Rita Jeptoo (Series VIII), and Jemima Sumgong (2017, Series X) were stripped of titles, with awards transferring to clean athletes like Edna Kiplagat. This shadow economy that taints elite competition fuels calls for systemic reforms well beyond simply eliminating incentives. I will outline such reforms below.

These stories—Ben Johnson’s arms race, Jeptoo’s deceit, Chepngetich’s disgrace—trace a continuum: from poverty-driven doping to elite fear of decline.

The sport’s current, fragmented system rewards winners, punishes decline, and offers no safety net for the merely human.

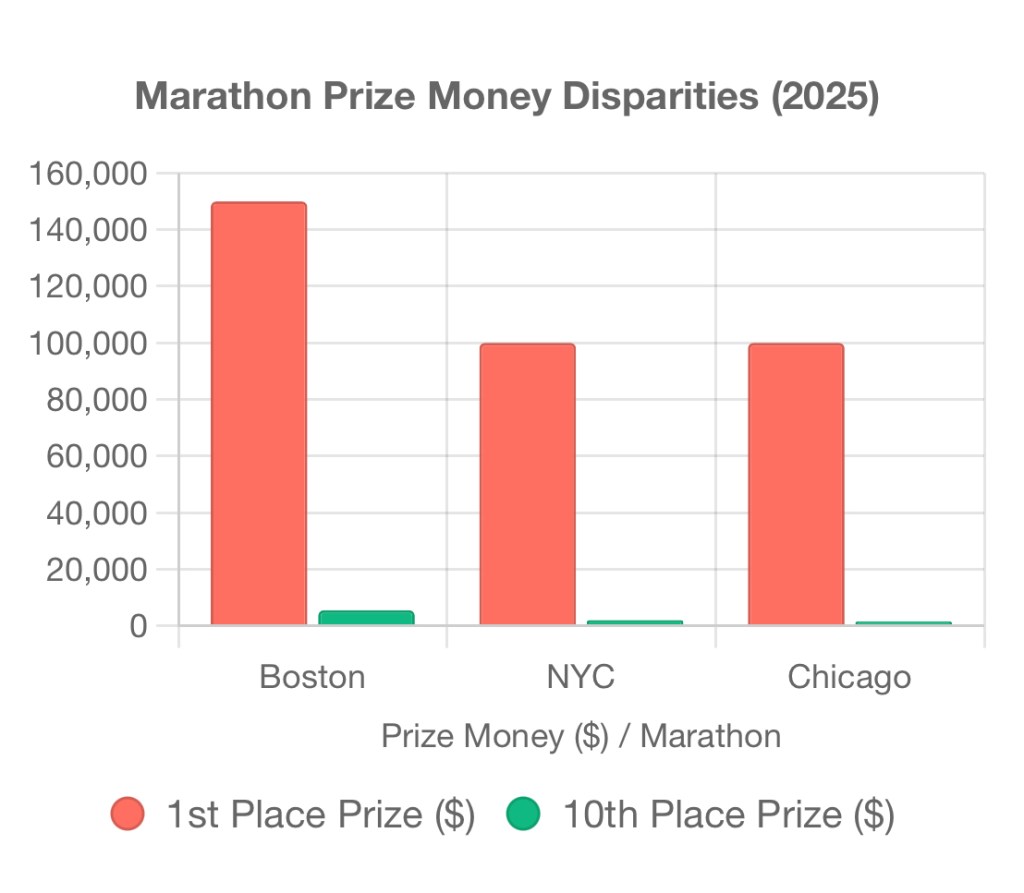

For young athletes without shoe contracts or appearance fees, when 1st to 10th place at even a Marathon Major drops from six figures to just over four, the pressure to reach the podium becomes immense.

Boston- $150,000 to $5500

New York – $100,000 to $2000

Chicago – $100,000 to $1500

⸻

Rebuilding Trust

Even clean champions bear doping’s shadow.

Olympic silver medalist Meb Keflezighi, who won both Boston and New York, helped coach his daughter’s high school team to a conference title this season. But he hesitates to step up in class.

“I’d really like to have a crack at coaching elites,” he says. “But you’re always afraid of what might happen in the next 20 hours. If they cheat, your name gets dragged in.”

His caution reflects a broader truth: suspicion is the tax on every success.

A haunting survey once asked: Would you dope for Olympic gold if it cost ten years of life? Ninety percent said yes.

That answer reveals doping not as pure deceit, but as an almost desperate yearning in a world where winning is all that counts.

⸻

A Fairer Way

Kenya’s running culture prizes humility and collective purpose.

Harambee—Swahili for “all pull together”—defines both community life and training groups.

A champion’s success builds houses, pays school fees, repairs churches. Failure ripples outward as communal disappointment.

Within that moral economy, doping can appear less like cheating than like taking stronger medicine—an act of misplaced devotion to family and village.

The global fight against doping has relied too heavily on punishing individuals and too lightly on understanding systems.

We measure morality in milligrams without measuring opportunity in dollars.

⸻

A More Structured System

What if the energy spent policing were redirected toward equity?

Toward education, nutrition, medical oversight, and post-career transition programs for those most at risk?

That’s how real deterrence begins—not through fear of exposure, but through faith in a future not dependent on it.

That would require a much wider funding base than the current seven Abbott World Marathon Majors, or the current circuit of independent, nonaligned races. It would require a professional league structure built around survivable integrity.

*

We’ve seen track experiment with new ventures—Grand Slam Track, the Athlos Women’s Circuit, and the upcoming USATF Series. People understand the old models need to be refreshed.

So imagine a World Road Majors Series—a professional framework that transforms road running from feast-or-famine into a stable career.

⸻

A Professional Framework for Integrity

1. Structural Foundation

A 25–30 event global circuit anchored by the World Marathon Majors, complemented by classic road races like the Great North Run and Falmouth Road Race.

A full-season calendar that sustains team-based athlete tiers and continuous media engagement.

2. Professionalization & Support

• Annual contracts provide base salaries, appearance guarantees, and prize floors.

• Centralized coaching, physiotherapy, and nutrition, ensuring world-class oversight as a standard, not a privilege.

• All under ethical supervision.

3. Integrity & Equity

Standardized year-round anti-doping protocols funded by the league itself.

Mandatory education and post-career support ensure integrity doesn’t mean poverty.

⸻

Who Pays for It

The biggest question is cost—and the answer lies in restructuring running’s economics. Today, the sport is completely decentralized, with athletes as independent contractors, races one-off opportunities, and shoe contracts at a premium.

Primary Funding: Media & Sponsorship Rights

• Centralized media rights: sell the 25–30 race circuit as one package to global broadcasters.

• Unified title sponsorship: one presenting sponsor funding the league’s integrity and salary base.

• Seasonal storytelling: rivalries, narratives, and athlete profiles that attract audiences and value.

Secondary Funding: Stakeholder Contributions

• Event fees from member races fund administration and anti-doping.

• Sporting goods manufacturers contribute in exchange for guaranteed access and co-branding.

• Health and wellness companies invest through corporate social responsibility programs supporting education and post-career transition.

Targeted Funding: Integrity Costs

• A dedicated anti-doping budget, administered by a neutral body like the AIU.

• Fines and forfeitures from doping cases recycled into education and testing programs—the cost of deceit funding the cost of integrity.

In essence, this would move the sport from a collection of loosely connected races to a unified, professional ecosystem where integrity is economically viable.

⸻

The Moral Reckoning

Running has always been the world’s most democratic sport—anyone with legs and will can enter.

But until fairness extends beyond the finish line to the starting conditions, the playing field remains tilted.

The quiet heroism lies not just in running clean, but in creating a world where doing so doesn’t come at the cost of your family’s welfare.

This is not to say poverty is a permission slip. Many runners resist temptation and keep their integrity intact. That resilience is where the true heroism lies.

I also recognize that reforming such a deeply decentralized sport isn’t simple. There are valid concerns, resource limits, and long-standing contracts and affiliations that complicate change. But complexity can’t be an excuse for inertia when the integrity of the game remains under threat.

The doping crisis in running isn’t about pure sport—that ideal died once athletics became a billion-dollar industry.

It’s about fair sport, where talent outweighs desperation.

You can’t police hunger—you have to relieve it.

And there’s no alchemy or punishment that can transmute fear into virtue.

To truly advance, the sport must make integrity survivable.

⸻

Editor’s note:

This essay will appear in The Quiet Heroism of Running: How Running Transforms Lives & Cultures — a collection exploring the long-run story of how miles became meaning, transforming millions of lives in the process.

END

This is entirely a road racing problem. The incentive in track isn’t there. Unfortunately it drags track down with it. And the major marathons are responsible. Either cut prize money by 90% or put it in escrow for a few years and any positive tests means no money.

Put the money in escrow for 5 years or so and give an annual amount to live on. Otherwise this problem is never going away.

Toni, I recall a meeting the late Bill Roe and I hosted during the USATF National meeting in Reno (I recall), several years ago.

We recognized that USATF, the RRCA and Running USA were all in their own silos. We gathered the available leadership together and proposed a business model that would include all three, highlighting and prioritizing their economic strengths.

The basic strategy was to enable corporate sponsors a “one stop shopping” opportunity to spread monies across the plateau of distance running.

A few gave polite head nods, but they all wanted thwir own independence and couldn’t envision a way it might work.

Your plan has such thoughtful merit. One could only wish that strong economic winds would fill those sails.

I have watched the “way out” desperation model in Kenya for decades. You correctly identified the terrible consequences of “why”. It is for that reason we created our small non-profit http://www.kiptureschool.org two decades ago. Grass roots academic growth creates better students, eventual local, the national leaders who can run their country in a more ethically correct way.

My solution is a microcosm and taken by itself creates hardly a ripple. I continue to contend that there are thousands of good-minded, financially able citizens of the world who might consider doing something similar.

Meanwhile, maybe, just maybe your broadbased model might be grabbed by the corporate community and get new legs!

Creigh

Creigh,

Thanks for sharing your experiences. I’ve been following what you’ve been doing in Kenya for years. It’s so praiseworthy. We started a small foundation, ENTOTO, to bring healthcare to Ethiopia after becoming enamored with the country through all our trips there with Mike Long and seeing the need.

It’s so interesting, isn’t it, that we can see how much better we train working in a group, even though we race as individuals. But for some reason, that Harambee, “all pull together” philosophy just can’t seem to take root in the world of road running.

I’ve always said that there are three things which motivate people in this world, money, power, and sex. I get the feeling that in our sport it isn’t the money and it isn’t the sex, but it is the power. Therefore, you have to convince people who came to positions of Power through the current system to give up part of that power to create a new system. And they just won’t do it. It comes back to NIMBY, not in my backyard. It’s all fine to do elsewhere, but we’re fine the way we are here.

It’s frustrating because we can see the loss of vitality in our sport even though it still remains incredibly robust in many ways. I think we had a big chance back in the 1980s with ARRA, but they couldn’t go all the way and settled for the trust fund model and never advanced beyond that. The sport never became professional as people understand professional. So we remain independent races with independent contractors and gain none of the synergy of group action.

Anyway, best to you and Renee. Stay well. Talk soon. Toni

This is an informative and compassionate commentary, Toni. The source of the problem is the ill-considered and self-interested model of professionalism that was forced through in 1981. The individuals may have been as heroic as they see themselves, but they created a system which rewarded only them, a small cadre of elite athletes, which did nothing for the ongoing development of the sport (hence the depressed years that soon followed) and did nothing to build a real profession. That means, as with law or medicine or music, one that rewards the whole range of those who contribute, not only the star counsel, surgeon, or singer, and one that insists on responsibilities as well as rewards. We could have a had a system that bans crooked agents just as crooked lawyers are banned. Instead, we have a situation where agents, race directors, shoe companies, and others make big money from poorly educated Africans, without accepting any responsibility when those runners commit infringements. At the very least (I argued in the Chepgn’etich debate last October), agents, race directors, etc should be responsible for giving public pre-race assurances that all the athletes are to the best of their knowledge free of PED.

We are left with this situation that you describe with such understanding, where it’s only the athlete who is cross-examined and punished.

The idea of making shoe companies responsible sounds like a bad idea. Why then would Nike or any shoe company go anywhere near the East Africans with their history better to dump them ahead of time.

And Grand Slam Track? More like Grand Scam Track. Sure they paid some after months of being harass…but anyone would be a fool to trust Johnson again. Whose reputation is in the toilet.

And Athlos big thing is having a pop star show up …and btw have a meet with a few events. Not sure how that works without a billionaire who likes to throw his money around. Knight does but he does it quietly. There is nothing at Hayward that mentions Knight or Nike.

Meanwhile…the Athlos guy basically is throwing a party with he and his wife at the center. I’ll pass.

And storytelling in track in the US has been proposed for decades. No one cares.

Too bad Kenya is such a poor country but I don’t see how a junior competition would stop the drug problem. They would be doping to get into that!

To solve the drug problem he major marathons could just not pay the elites. No money no incentives!

The majors these days are just big jogathons with an endless supply of recreational runners who pay gobs of money and couldn’t give a toss about who won. The Chicago Tribune barely mentioned the winners. Meanwhile The Big Elite Story is the positive test by the WR holder. Who needs that publicity.

Fwiw I think Athletics is actually doing pretty great these days. The WCs in Japan were very entertaining with big crowds. Jake Wightman’s comeback in the 1500 was a huge story in Britain.

The DL is popular in Europe and Pre Classic was incredible with a sellout. And the Trials in Eugene were fantastic.

I’ve known quite a few top Kenyans going back to Simeon Kigen in Boulder. Nice people but with Cole Hocker and Sydney and their spectacular stuff who needs the Kenyan road runners these days.

Conrad Truedson

Eugene

Toni (and Barry!), Thank you both for articulating and highlighting a dilemma that for many years has clouded our sport. But we need to remember that it’s not just a T & F problem but ubiquitous in all of sports. I can’t even take a wild stab at how many H.S. football players are on some version of a PED. College? Pro? Fugedaboutit! I don’t see a way out. The $$ temptation is too great. I’m glad I’m just old enough to recall when Sports were still clean.

Hey Toni,

This is one of the most well thought out pieces I have ever read. Your love for the sport, and a longing for times past comes through, along with a step by step plan of what has to be done to make this sport fair.

Anyone born in this country cannot even begin to conceptualize living without electricity or indoor plumbing. The idea that a single marathon victory can bring electricity to an entire community is impossible for anyone in an industrialized nation to grasp.

I think your plan is not only very sound, but also incredibly humane and compassionate. However, it will take time, a lot of time to implement it, and I’m not so sure the sport can afford it, the time that is. Here are my thoughts on the doping crisis:

Barry J. Lee

Barry, thank you for the well considered reply. And I agree with you, the penalties must convect upward through the chain to where it may have some affect. Sanctioning the individual athlete has proven ineffective in controlling the problem, much less eliminating it.

I also agree that if they can provisionally sanction the athlete, then, with evidence in hand of wrongdoing, the precedes or record run, they can also provisionally suspend that record until the full adjudication of the case. To allow the Record to stand out there only invites the same doping that likely produced it. It exacerbates the problem rather than solving it.

fully aware that changing this deeply ingrained system will be difficult. But if the ongoing crisis that devalues our sport so greatly isn’t motivation enough to change, then what would be? At some point, as Lincoln said in his 1860 campaign imploring the south to think of the mystic chords that bind rather than sectional allegiance, road races have to see that working together is the only way out and a way to grow the sport, retain its integrity, and maybe assist in developing a better generation ahead.

Again, thanks for reading and replying. All the best toni