Advanced age brings its own rewards, even as it reminds us there’s more behind than there is ahead. As we embark on yet another lap of the sun, I thought I’d recall an early memory of what would become a life immersed in sport, which has always been my passion and refuge.

***

I was just 10 years old when we abandoned the suburbs, a family swimming hard against the tide of white-flight emptying the urban centers of post-World War II America.

It was April of 1958, midway through Ike’s second term in the White House. Bob Pettit had just led the St. Louis Hawks to their only NBA title with a 50-point game-six clincher against the defending champion Boston Celtics, while St. Louis Cardinal baseball slugger Stan Musial was a month away from notching his 3000th career hit again the rival Chicago Cubs.

I was a fourth grader at Barat Hall, the oldest all-boys private primary school west of the Mississippi River. Everything in St. Louis was the oldest whatever west of the Mississippi River. The oldest statement ever made west of the Mississippi River was that something, whatever, was the oldest whatchamacallit west of the Mississippi River.

Anyway, Barat Hall was appropriately ancient on the far side of the Big Muddy, nestled in the city’s tony Central West End, about two miles north of our Shaw neighborhood in the city’s near South Side.

We had spent the previous seven years in St. Ann, one of many new suburban developments that sprung up like mushrooms for returning vets and their growing broods after World War II.

Tucked out along 1-70 close to Lambert St. Louis Airport, for me, St. Ann was perfect: kids all around, a nearby woods, candy beyond measure on Halloween, and ball fields where I played Little League and watched semi-pro games with my dad on summer weekends.

But with our five-member family growing in age and size, the tiny, two-bedroom bandbox of a house on St. Girard Lane was no longer adequate. Plus, with her aristocratic Polish background, Mom wanted to live in a more stately setting, perhaps near a park to remind her of ancestral home in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains in the southeastern corner of Poland.

The house on Flora Place, though by no means stately, was, at three-floors, four bedrooms, and 2526 square feet, a nice step up. Plus, at the top of the street, just two blocks away, sat the 79-acre Missouri Botanical Garden, while six short cross blocks to the south was the 289-acre Tower Grove Park, the second largest green space in the city.

The house on Flora Place, though by no means stately, was, at three-floors, four bedrooms, and 2526 square feet, a nice step up. Plus, at the top of the street, just two blocks away, sat the 79-acre Missouri Botanical Garden, while six short cross blocks to the south was the 289-acre Tower Grove Park, the second largest green space in the city.

Plenty there to like. But since my older sister, Teresa, younger brother, Marek, and I attended private Catholic school outside the neighborhood, moving meant having to make new friends by means other than the local schools.

For me, that meant sports, as I had always been an accomplished runner, jumper, and thrower, whatever the season, whatever the sport. What I wasn’t quite as adept at was removing myself from the house via parental permission to display said acumen in running, jumping, and throwing.

So, there I was on that first Saturday since we moved in, all pink-cheeked and poised, standing in the foyer by the front door, massaging the well-oiled pocket of my Harvey “The Kitten” Haddix Rawlings baseball glove.

So, there I was on that first Saturday since we moved in, all pink-cheeked and poised, standing in the foyer by the front door, massaging the well-oiled pocket of my Harvey “The Kitten” Haddix Rawlings baseball glove.

Out front, across the parkway that bisected Flora Place, two boys about my age were playing a game of catch.

As I watched their ball ripple back and forth through the bevel-edged glass of our front door, I remember thinking for the first time, “maybe this place might be salvageable after all.” And I began fashioning a plan to get out there and join them.

And I’m telling you, I actually thought I had a prayer of pulling it off. Yet, down deep, there remained a nagging sense that my chances were short. So, I needed to act fast. Because despite all the societal advantages of our Baby boom generation, we did not grow up in a child-centric universe.

After a long centering breath, I tucked my mitt under my left arm, then began turning the front door knob as gently as I could to release the latch.

Man, I tell you, this was as about delicate an operation as any ten-year-old was capable of. And if it had worked, who knows, I might’ve turned into a brain surgeon or something. Not that we ever had any scalpel-wielders swinging from the family tree, so the odds weren’t all that great. Still, at age 10, who can rule out genetic trailblazer? It happens. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

I kept pulling on that doorknob with as gentle and constant a pressure as I could, trying like hell to loosen the hold.

You see, I’d learned in that first week that the weather strip along the front door jamb held as tight as a newborn triplet to a mother’s nipple. Only a firm yank was going to release this baby.

Problem was, whenever the heavy front door released from the weather strip forming the barrier with the sill below, the vacuum between the front door and the storm door would break as well, causing the storm door to rattle on its frame.

Ten-year-olds, I need not remind you, were not well served by impressively noisy entrances and exits during the second Eisenhower administration.

“Come on, baby,” I muttered. “Give it to me.”

I peaked over my shoulder; voices, but none approaching. The coast remained clear.

From this far remove, I can easily see how this was another of those losing battles of hope against experience. Notwithstanding, I kept at it, valiant for freedom, hoping that I could catch the moment just right.

Of course, I didn’t, and my hopes sank like last semester’s grades as the door’s eventual release brought an audible Woosh! breaking the seal and causing the storm door to rattle on its frame like an aging spaniel with heart worm disease.

I let out my held breath and waited. Sure enough, down the stairs they came, the three family dogs barking wildly. Move to Plan B.

“I’m going out front,” I said with as little voice projection as possible, as I zipped my windbreaker up over a blue hooded sweatshirt.

My intention was to announce my exit obliquely, then get out before either parent realized I wasn’t asking either of them for permission directly. That way, even upon capture, one could honestly plead innocence, having inferred permission from the joint silence. Didn’t always work, but it gave me a hell of a better chance than really asking, because that never worked.

Mom was upstairs correcting French tests for next week’s classes at City House, the all-girls sister school to Barat Hall, where she taught French and math. Pop, along with my younger brother, Marek, and older sister, Teresa, were cleaning old wallpaper in the dining room downstairs.

Since moving in, we spent much of our time cleaning, unpacking, and finding our way around the new surroundings.

While Pop, Marek, and Teresa were handling wallpaper matters in the dining room, I had been assigned some other task – rearranging dust motes in the living room, I think, though I’m not really sure.

Being less anal about such matters than the folks, I felt like I had accomplished my task, thus freeing me for more private concerns, like playing catch outside.

***

Stepping out onto the cracked mosaic of blue and white hexagonal tile that covered the front porch, I felt the graying wind blowing through the barren branches of the trees out front, conditions that reminded me more of the winter past than the warmer months ahead.

Stepping out onto the cracked mosaic of blue and white hexagonal tile that covered the front porch, I felt the graying wind blowing through the barren branches of the trees out front, conditions that reminded me more of the winter past than the warmer months ahead.

I walked down the first flight of five stairs toward the sidewalk, bouncing a tennis ball as I went. The sound of that tennis ball rebounding off the pavement would be my opening salvo in my grand plan.

Built in the first decade of the 20th century, the brick and stone homes lining the six-blocks of Flora Place rested 50 yards across from one another past sloping front yards, the streets, and the parkway between. An arch of mature sycamore and maple trees along the parkway and bordering the sidewalk filtered the sun on sweltering summer days.

As I bounced my tennis ball, I kept a side eye on the two boys across the street. They were alternating skidding ground balls along a concrete infield with long, looping fly balls arced high into the tree-sprouted outfield.

I’d seen a few kids since moving in, but hadn’t had a chance to make any friends so far. The plan today was to toss the tennis ball up against the face of our front steps so the other kids would see that a fellow athlete had moved in across the street. Then, if my ball hit the point of one of the stairs and sailed over my head into the parkway, in retrieving it, I might make contact and bingo, they’d ask if I wanted to join them. A damned fine plan, too, if I do say so.

I had already established my throwing rhythm out front playing step ball, creating a steady ‘kuh-pock’, ‘kuh-pock’ of the tennis ball rebounding off the face of the steps leading off the porch, then skipping off the walkway, before landing in my mitt as I stood along the sidewalk below the second short flight of stairs.

The sound drew the attention of the kids across the way, just as I had planned. But it also drew Mom’s attention upstairs, which I hadn’t planned.

Suddenly, her voice rang out from an upstairs window, cutting short my dodge as the dogs yapped incessantly behind the front door.

“Toni?”

“Yes, Mom?”

“What are you doing?”

“I’m just tossing the ball around out here,” I called up to the bay window on the second floor while maintaining my easy throwing motion.

Kuh-pock went the ball as it bounced off the front face of the step then the walkway and into my Rawlings mitt.

“Some kids are playing catch across the street. Kuh-pock. They’re about my age. I’ll just be out front. Kuh-pock. Maybe end up playing with them.” Kuh-pock.

Afraid to fully look up, I could sense Mom taking her weight on her palms as she leaned on the sill as she peered out. When she spoke, her tongue still struggled with the bend of syllables still new to muscles tethered to her consonant-rich native Polish language.

“Isham?” she said, turning to head downstairs for support – as if she ever needed that. “Toni is outside.”

And there you had it. Toni is outside. You can imagine the domino effect that might have on the free world. Yet, I couldn’t help wonder, exactly how big a deal could it be for me to be right in front of the house?

Back on the sidewalk out front tossing my tennis ball, I still held out hope. I maintained my cool throwing technique, using a full shoulder turn and easy release. Kuh-pock. No big velocity involved, you see. Kuh-pock. But certainly the suggestion that it was there any time I wanted it. Kuh-pock.

“Tone?”

Pop had come to the front door wearing a pair of his army khakis trousers and a plaid wool shirt.

He stood nearly 6’2″ tall, and with his stentorian, cultured voice created a presence of command and respect. “Have you finished your work?”

“Yes, I have,” I replied, holding onto the ball now, though tossing it reflexively into my mitt, feeling justified in my play.

“Who are those boys over there you are talking about?” Mom again. “And do we know their parents?”

Oh, God. Here we go. Mom and Pop weren’t the type to trifle with, obviously, but…

“Mom, I’ll have to say, I don’t think so.” (And is there a correct answer here? Do you know their parents? I don’t know. You’re still trying to find the light switch in the bathroom at night, aren’t you? We just got here. You want to play with the parents, go meet them yourself. Besides, they aren’t playing ball.) None of which I said out loud, of course.

“Because we won’t have you associating with the peasant children,” Mom explained, having joined Pop on the porch.

Ah, the real rub, peasants.

“Okay,” I thought to myself, while trying to crystallize a new game plan for extended freedom. “Let me get this straight. I’m ten, you move the entire family twenty miles away from where all my friends were, and now you won’t let me go play with the Italian kid who lives across the street who is my age, probably Catholic, and plays baseball? Is that it? Have I identified the madness? Perhaps someone should have canvassed the neighborhood before I got moved out of the only home I had ever known!”

“Mom, come on,” I said in a whiny voice instead, knowing sarcasm, even though fully clothed in logic, couldn’t possibly elicit a positive outcome. But at least I kept the whine low so the guys across the street couldn’t hear.

“I’ll give you a full report when I find anything out. But I gotta meet them first, right? Come on, Puh-leeeese.”

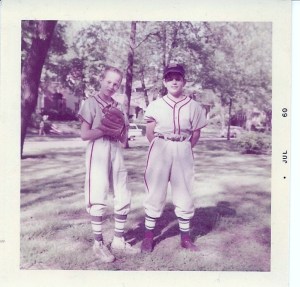

Fran Cusumano, Danny Slay

Bob Brunner, Toni Reavis

Well, I finally did engage with all the kids on the block, and to this day still keep in contact with our League of Friends, as we called ourselves. Great times we had. Great memories we shared. Here’s hoping everyone experiences equally fine ones in 2025. Thanks for continuing to read the blog.

END

Ok, it was a pretty poor plan, I know. But hey, I was ten. Give me a break.

Yes, Toni, great piece, loved it. League of Friends, what a great name.

I’ll be watching for “the book” in 2025.

good memories, Toni. I’m a few years ahead of you, but remember the days of pickup baseball. And, the Harvey Haddix card brings back memories of his 12 inning perfect game and drastic end. So, you must be a lefty?

Loved this Toni!! Such a wonderful “slice of being ten” piece.