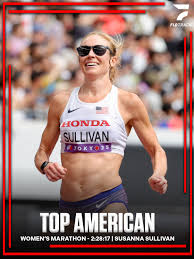

In the opening days of the 2025 World Athletics Championships in Tokyo, American marathoner Susanna Sullivan reminded us what quiet perseverance looks like. A sixth-grade math teacher by trade, Sullivan led the women’s marathon for over an hour and a half before being overtaken. But she didn’t fade—she rallied. Her fourth-place finish marked a 54-position improvement from Budapest two years ago.

“You don’t always get the day you trained for,” she messaged afterward, “but damn, it feels good when you do.”

That sentiment resonates far beyond the racecourse. In a time when many Americans feel left behind—by politics, by economics, by the fraying social contract—Sullivan’s run offers a metaphor for civic life. Progress isn’t always linear. Recognition doesn’t always come. But showing up, staying in stride, and finishing strong still matter.

Sullivan’s performance reflects deeper themes of endurance, adaptation, and shared purpose that shape our democracy. It’s a meditation on what it means to lead quietly and with purpose, to fall back without giving up, and to find dignity in the effort itself.

The American Dream as a Long Run

Running teaches us that endurance alone isn’t enough. Nor is speed. It is the intricate balance of both that produces results. In the marathon, the marriage of endurance and speed becomes even more critical when it’s time to land medals.

After passing Sullivan, 2021 Olympic champion Peres Jepchirchir of Kenya counter-punched her way to gold, out-dueling 2024 Olympic silver medalist and former world record holder Tigst Assefa of Ethiopia by two seconds in 2:24:43, in a white-knuckled battle over the final 350 meters. Julia Paternain from Uruguay secured the bronze medal, marking a historic breakthrough for Uruguay as the country’s first-ever medalist in athletics at the World Championships.

America’s Susanna Sullivan and Jess McClain led early—Sullivan till 28km—before relinquishing the lead. But both rallied beautifully, with 35-year-old Sullivan finishing fourth, and McClain in eighth in the warm, humid Tokyo conditions.

The American Dream has always been like Sullivan’s race—not a sprint, but a long run shaped by effort, sacrifice, and belief in a better future. For generations, that belief shaped our social contract: citizenship for belonging, contribution for dignity, opportunity open to all who’d chase it.

The term “American Dream” was first popularized during the Great Depression by James Truslow Adams in his 1931 book “The Epic of America.” In it, he described “that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement.”

When the Course Got Harder

Even in the dark days of the 1930s, when nearly a quarter of the American workforce was unemployed, the dream of a better tomorrow still sustained a nation in crisis. FDR’s New Deal instituted marketplace reforms and leveled the playing field for the middle class.

Today, however, the American Dream seems more mirage than oasis for many, the road ahead clouded with mistrust and doubt.

Political polarization runs as deep as it has since the 1960s. Economic inequality isn’t just widening—it’s hardening, with the top 10% holding nearly 70% of the nation’s wealth while child poverty remains stubbornly high.

When Franklin Roosevelt took office in 1933, only 15% of Americans belonged to the middle class. By 1971, 61% of Americans had risen to that station. In 2023, that figure had fallen to 51%.

Today, trust in government sits at historic lows—barely 30%—and politically motivated violence has tragically spilled from the hot-houses of internet forums into the streets. The bonds that carried us through depressions and wars are fraying, replaced by tribal loyalties and digital echo chambers. And our leaders seem more intent on trading on those divisions than looking to heal them.

Like any marathon runner knows, the distance is never easy for everyone. America’s social contract was never universal. Even the New Deal excluded many Black and brown Americans by omitting agricultural and domestic workers. Redlining locked entire neighborhoods out of generational wealth. Women and immigrants faced barriers that limited their share of the promise.

Yet, the postwar era delivered major gains. Median family income nearly doubled from 1946 to 1978. Union membership peaked at 35%. College remained affordable, homeownership expanded, and public investment stitched communities together. Upward mobility, though imperfect, felt possible.

By the late 1970s, the ground had shifted. The 1973 oil embargo ended the era of inexpensive fuel. Deindustrialization erased millions of manufacturing jobs. Deregulation and globalization lowered consumer costs but hollowed out communities. Union membership collapsed to 10%, wages stagnated, while CEO pay exploded.

The 2008 financial crisis exposed the fault lines: Wall Street got bailouts, Main Street lost homes. Many concluded the system no longer worked for them. Housing costs soared, student debt ballooned, and civic groups—from unions to churches to bowling leagues—dwindled, leaving fewer spaces for shared purpose.

Finding Our Stride Again

Still, in the rhythm of Sullivan’s long run, there remains stubborn hope. Progress is slow, but possible. A runner adapts to the course and competition, and so must we.

Like Sullivan’s rally in the final kilometers, renewal starts with concrete steps, like updating labor laws to account for gig workers, restoring collective bargaining, funding childcare and education. It also means ensuring fair and representative elections through reforms like ranked-choice voting to broaden candidate outreach beyond cloistered congressional base camps. These aren’t just policies—they are commitments to one another.

Immigration remains a source of strength as it has throughout our history. Immigrants make up 17% of the workforce, from farmworkers to tech innovators. But integration—being American, not just living in America—demands investment in language programs, apprenticeships, civic participation. Where states have embraced this approach, like Minnesota, economies have thrived.

Yet laws alone won’t mend the contract. French philosopher Ernest Renan once called a nation a “daily plebiscite”—a daily choice to remain together while building on shared communal memories. That requires rebuilding civic spaces—councils, centers, forums designed for dialogue instead of division.

Free markets have their place, but they must serve people, not the other way around. The social contract thrives only when workers share in the gains, when effort leads to opportunity, when the finish line remains visible to those still running.

The Race Continues

Running teaches us resolve and adaptation. As runners, we read the pack, adjust to the course. Our Constitution endures not as a relic but as a living framework, continuously revised to include those once excluded. Today’s challenge is to see the marginalized—whether displaced workers or new arrivals—as teammates, not rivals, much less replacements.

Sullivan’s fourth-place finish in Tokyo won’t make many headlines, but her performance embodies something essential: the dignity of sustained effort, the grace of leading when possible and persevering when passed, the understanding that the race itself matters as much as the result.

The American Dream isn’t a solo dash—it’s a relay. The test isn’t winning a sprint but keeping the race alive, together, for ourselves, and those yet to come.

In a time of division and doubt, Susanna Sullivan showed us what that looks like: teacher by day, world-class athlete when called upon, American dreamer always—leading when she can, rallying when she must, finishing strong regardless.

End

Toni, well done.

We certainly need civic endurance to keep moving in the right direction as a nation.

We must never give in and, as you say, “find our stride again.”