Great question — and one that gets to the heart of elite pacing strategy and physiological sustainability.

John Korir entered the 2025 Bank of America Chicago Marathon as defending champion (2:02:44) and fresh off an easy Boston win (2:04:45). His goal: break 2:01 on the same course where Kelvin Kiptum ran his world record 2:00:35 in 2023.

Though the overall field was strong, Korir’s primary competitor promised to be half-marathon world record holder Jacob Kiplimo of Uganda, who was running in only his second marathon after finishing runner-up at the London Marathon this spring in 2:03:37.

The weather in Chicago was good—54°F / 12.2°Celsius—but there was a tricky 9 mph SE wind to decipher. On Chicago’s mostly north-south loop course, the wind would be both an advantage and a detriment. The advantage came in the first third and then in the final 5km. But along much of the second half, it would come at you after your early strength has been already put into service.

Jacob Kiplimo – 2:02:23

Based on the way the race turned out, with John Korir eventually dropping out after a blistering start (13:58-5km, 28:25-10km, 60:16-first half) and Jacob Kiplimo winning in 2:02:37 but slowing dramatically in the final kilometers after being on world record pace through 35km (1:39:53 vs. 1:40:22) the question of optimum pacing continues to be an intriguing one.

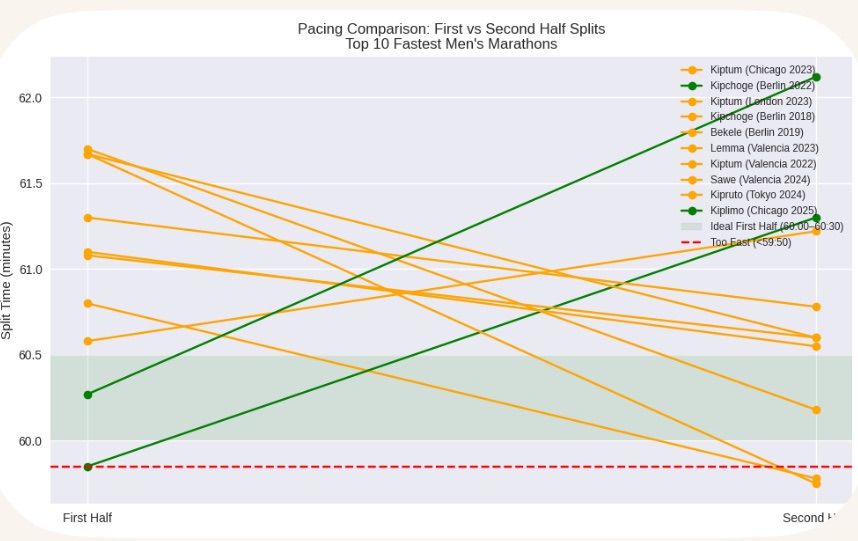

Based on the splits from the top 10 fastest men’s marathons, we can draw some clear insights about what’s “too fast to hold” and what’s optimal for a sub-2:00 finish.

🧠 What the Data Show

Let’s look at the splits of the top 10 performances:

Athlete/ Event/ Time/ 1st Half/ 2nd Half/ Negative Split?

Kelvin Kiptum (Chicago 2023) 2:00:35/ 60:48/ 59:47/ ✅ Yes

Eliud Kipchoge (Berlin 2022) 2:01:09/ 59:51/ 61:18/ ❌ No

Kelvin Kiptum (London 2023) 2:01:25/ 61:40/ 59:45/ ✅ Yes

Eliud Kipchoge (Berlin 2018) 2:01:39/ 61:06/ 60:33/ ✅ Yes

Kenenisa Bekele (Berlin 2019) 2:01:41/ 61:05/ 60:36/ ✅ Yes

Sisay Lemma (Valencia 2023) 2:01:48/ 60:35/ 61:13/ ❌ No

Kelvin Kiptum (Valencia 2022) 2:01:53/ 61:42/ 60:11/ ✅ Yes

Sebastian Sawe (Valencia 2024) 2:02:05/ 61:18/ 60:47/ ✅ Yes

Benson Kipruto (Tokyo 2024) 2:02:16/ 61:40/ 60:36/ ✅ Yes

Jacob Kiplimo (Chicago 2025) 2:02:23/ 60:16/ 62:07/ ❌ No

🔍 Insights

- Ideal Range: Most successful sub-2:02 finishes had first-half splits between 60:35 and 61:40, with negative splits in the second half. Seven of the top 10 times ever run have come on negative splits. Irrespective of technological advances, the marathon punishes front-loading.

- Sub-60 Half Split: Kipchoge’s 59:51 in Berlin 2022 was the fastest ever opening 21.1 km. With his INEOS 1:59 Challenge exhibition success in Vienna 2019, history’s first legitimate, record-certified sub-2:00:00 marathon was hanging like a big ripe fruit past the Brandenburg Gate. But he slowed in the second half—running a 1:27 positive split—though still breaking his own 2018 world record by 30 seconds.

- Kipchoge’s record lasted until Kelvin Kiptum‘s 2:00:35 in Chicago 2023, which he polished off with a 61–second negative split (60:48/59:47). His debut in London in 2023 produced a nearly 2 minute negative split, resulting in the first—and still fastest—sub one-hour second half marathon (59:45). Kiptum also holds the third-fastest second half with his 60:11 close in Valencia 2022. The interesting corollary is that he also holds three of the four slowest first-half splits of the top 10 performances in history (61:42, 61:40, 60:48).

- Even though the record book has been completely rewritten in recent years—based largely on super shoes and super nutrition—the adage: “going out too hard too soon will break down the machinery” still holds true.

✅ Optimal First-Half Split for Sub-2:00

We know it’s coming soon, but based on the three marathons he ran before his untimely death in January 2024, don’t you think that Kelvin Kiptum would have already gone sub-2:00:00 by this time in his career? It is still sad to think about.

Sub-2 requires an average pace of 2:50/km or 4:34/mile. That means:

- Target Half Split: 60:00 to 60:30

- Why: This allows for a slight negative split or even pacing, without risking burnout. It’s a fine line.

- Too Fast: Many people point to the 2008 Beijing Olympic Marathon as the Rubicon runners crossed from being wary of, or even afraid of the marathon, to dismissing its dangers. In the heat and humidity of that Beijing summer day, Sammy Wanjiru attacked from the gun, then surged continuously throughout the distance. It was a profligate spending of fuel and seemed fraught with potential disaster. Yet Sammy never faltered, finishing nearly a minute ahead of Jaouad Gharib of Morocco, as he came home with Kenya‘s first Olympic Marathon gold medal.

- But it was London 2009 that really changed the way the marathon was run. After Beijing 2008, nobody was going to let Sammy just go running off on his own anymore. The pack went with him through a no super shoes, no sodium bicarbonate 28:15 opening 10km and 1:01:36 first half. Yes, they slowed dramatically in the second half, though Sammy still set a course record of 2:05:10. But what’s significant is that his great rival and Olympic bronze medalist, Ethiopia’s Tsegaye Kebede, crossed just ten seconds back in 2:05:20, while Jaouad Gharib finished seven later. They might’ve crashed a little in London 2009, but that race established the attacking mentality of marathon racing that lives with us to this day.

- In the pre-super shoe era, sub-1:02 was the line one dared not cross if you hoped to finish strong. Since then, technology has redrawn the limits, bringing that danger zone closer to one hour flat. The data now suggest that anything faster than 59:50 remains unsustainable — at least for now. But that won’t last. Human striving is relentless. Refusing to accept the impossible means attempting everything! Onward!

END

Toni – thanks for compiling this data. I’ve been thinking about this is a lot recently particularly as they regularly announce the 13.1 target for the pacers at the majors. That elusive negative split is the thing here, and, just like when your high school coach tried to get you to not go out too hard, its difficult to convince many of these runners to not “go out hard and hang on” because, as you noted, it doesn’t work at even a world class level. Great knowledge here.