The Boston Marathon sings a sweet song of speed within its test of endurance, its melody beginning with the marching drum-and-fife call to the line in Hopkinton on Patriots Day morning.

At the starter’s gun, the g-force fall out of Hopkinton in the very first kilometer tempts runners with an ease that conceals its cruel price: the shattering impact on the quadriceps by the time Boston’s Back Bay towers come into view 21 miles later.

At Boston, one learns that speed isn’t free. Any reckless embrace of gravity’s promise can lead to bitter lessons. Yet, properly raced, Boston can still produce fast times. Notwithstanding, the ancient route remains ineligible for record purposes due to its point-to-point and net downhill layout.

Boston’s overall reputation is not that of a fast marathon by modern global standards. The Association of Road Race Statisticians doesn’t rank it among the top 15 fastest courses. Boston’s speed is a different measure altogether—a test of resilience and mastery over its undulating terrain and shifting winds.

Bill Rodgers, four-times a champion, summed it up: “To run fast here, you need cool weather, a west tailwind, and the marathon gods smiling.” Those conditions, he noted, only align about once every decade.

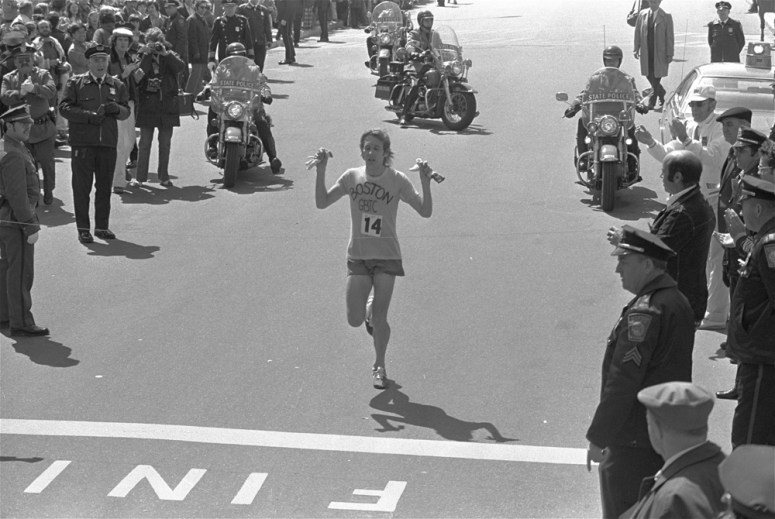

1975 was one such year when Rodgers, clad in a hand-stenciled gray tee shirt and oversized painter’s gloves, broke both the American and course records. His 2:09:55 came despite four stops to drink water and to re-tie a loose shoelace.

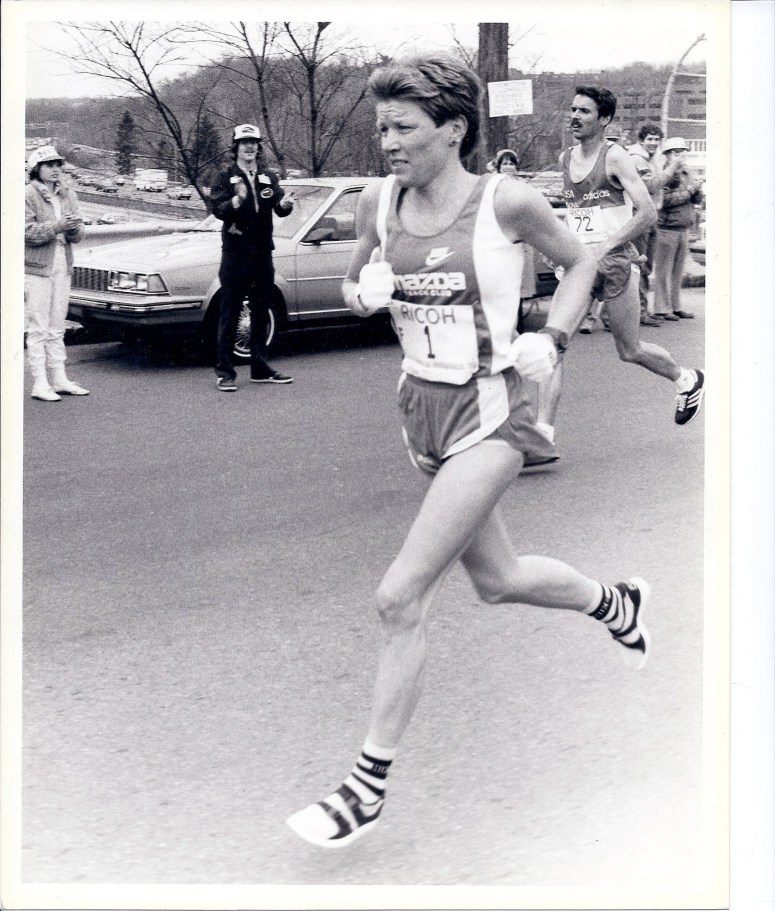

Joan Benoit found her own perfect storm in 1983, attacking the course with a 1:08:22 first half and finishing in 2:22:43—slashing two and a half minutes off the world record tied earlier that day in London by Norway’s Grete Waitz.

But for every historic triumph, there are years when Boston’s hills and weather humble even the greatest athletes.

Everyone in the field learned that lesson in 2018 when near hurricane conditions lashed the area and almost caused the event’s first-ever weather cancellation. Fortunately, BAA officials understood the inner workings of their field all too well, and realized the runners would go out and run the race course no matter what they said. Japan’s Yuki Kawauchi (2:15:58) and America’s Des Linden (2:39:54) survived to wear the wet olive wreath crowns.

HARD TRUTHS

Norway’s great Grete Waitz learned the truth about Boston the hard way in 1982 in her only attempt in the Hub. Through much of the race, the world record (2:25:28, Allison Roe, NZL, New York City 1981) seemed within Grete’s grasp as she sped toward Boston’s Back Bay at 2:23 pace. But the sirens of speed—and her own lack of careful study—led her into the shoals of disaster. Though a multiple time World Cross Country champion, Waitz hadn’t trained specifically for Boston’s early downhills.

“Even before Heartbreak Hill, my quads were gone,” she confessed. “It was a relief to run uphill. By 24 miles, I couldn’t move my legs.”

Or, take her countrywoman, Ingrid Kristiansen, the women’s world record holder from London 1985 (2:21:06) who won Boston in 1986 and 1989. Both years, the Norwegian powerhouse sought to become the first woman to break 2:20. But Rodgers’ aforementioned Marathon gods were not smiling on either occasion, and high temperatures thwarted her attempts. Though she won by 3:00 in 1986, then 4:31 in ‘89, her 2:24s came nowhere near her historic goal. “Boston is tough,” she admitted. “It’s no joke.”

INTRODUCING SPEED

Rhode Island’s Les Pawson (winner in 1933, ‘38, ‘41) and Boston University grad John J. Kelley (1957) introduced track training to the marathon. Both men set course records. But Boston’s modern era began most definitely with Bill Rodgers’ first of four victories in 1975—being celebrated in 2025 in its golden anniversary.

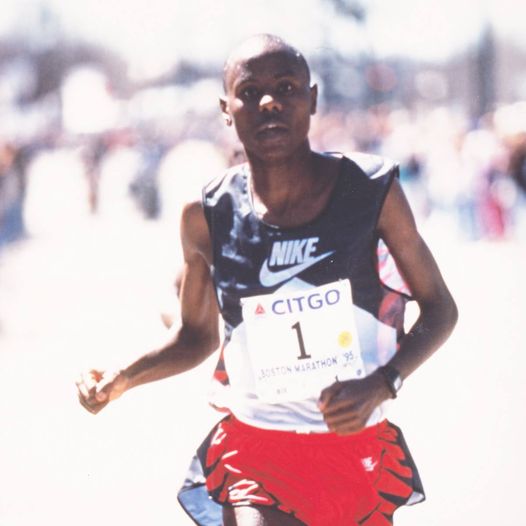

The marathon as a speed event extended through the famed “Duel in the Sun” between Alberto Salazar and Dick Beardsley in 1982, producing the event’s first two sub-2:09s. It developed further with the arrival of Kenya’s Cosmas Ndeti in 1993.

In the first of his three straight Boston wins, 22-year-old Ndeti followed his better known and more experienced cousin, Benson Maysa, for the first 25K, sitting off back of the lead pack. Only after Benson told Cosmas that it wasn’t his day and that his cousin should go on without him did Ndeti shift into racing gear.

Throughout the next 17 km, the Kamba tribesman from Machakos, Kenya, caught and passed the four men in front of him, including Korea’s Kim Jae-Yong and finally the leader, Luketz Swartbooi of Namibia, with one mile to go.

With his second half chase, Ndeti produced the first negative-split victory in Boston history (1:05:13 / 1:04:10). The next year he took down Rob de Castella’s 1986 course record (2:07:51) by 36 seconds, then won again in 1995. Only hubris kept him from a four-peat in 1996.

NO RESPECT

1996 was the 100th running, and the excitement for the centennial celebration was palpable. A record 38,000 runners crammed into Hopkinton as the BAA opened the race for the historic occasion.

Ndeti was brimming with confidence, an unusual display for the normally soft-spoken Kenyan runners. Throughout race week, he openly declared his intention to win and break the world record (2:06:50, set by Ethiopia’s Belayneh Densimo in Rotterdam 1988).

From my journal #56 – Mon. 15 April 1996.

“Awaken to a bright, sun-splashed, but cool morning for the hundredth running of the Boston Marathon. Laced by a moderate sea breeze, the course will not avail fast times today. Despite 54°F in Hopkinton, 46°F in Boston shows the wind is blowing in off the ocean and will deter speed, especially from 17 miles to the finish.

Notwithstanding, the cocky three-time champion and 1994 course record holder (2:07:15) has been guaranteeing victory all week, and sprints right to the front.

4:36 for the 1st mile. 28:20 at 6 miles (2:03:34 pace). Too fast, too much leading into the 10-15 mph east-southeast sea breeze. He lost respect for the marathon, trying for something special on an uncooperative weather day. 1:03:22 at halfway. Watch out!

Fellow countryman Moses Tanui and Ezequiel Bitok attach tow lines to Ndeti, then overtake the fading champion down Beacon Street. From there, they battle shoulder-to-shoulder into Kenmore Square before Tanui, second in 1995, opens his 10-second winning margin at 2:09:16. Ndeti finishes in third, 35-seconds back. He could’ve won if he had just tucked away from the wind for a few miles. 1:03:22 at halfway on a 1:05 day.

“He thought he was God,” said 1986 champion Rob De Castella.

*

Four-time champion (2003, 2006, 2007, 2008) Robert Kiprotich Cheruiyot dominated an era when Boston became synonymous with Kenyan brilliance. His 2006 victory ended Cosmas Ndeti’s course record run of 12 years by a single second at 2:07:14.

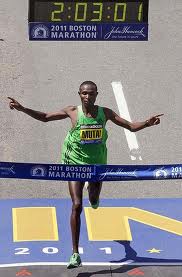

Then came Geoffrey Mutai in 2011. On a day when a 16-20 mph west-southwesterly tailwind pushed runners down the course like a fast-spreading rumor, Mutai redefined Boston’s possibilities. When the marathon world record stood at 2:03:59 (Haile Gebrselassie, Berlin 2008), Mutai’s 2:03:02 shook the sport to its core while shattering the previous course record (2:05:52 by Robert Kiprono Cheruiyot, 2010) by 2:50.

Boston had only produced one men’s world record before the rule changes removed the course from record eligibility: Suh Yun-bok, 1947, 2:25:39. 2:03:02 was the fastest marathon ever run by nearly one minute in 2011, and the third largest reduction in Boston’s course record after John J. Kelley’s 5:34 reduction in 1957, and Ron Hill’s 3:19 erasure in 1970.

Though not recognized as a world record, Mutai’s feat was a masterclass in speed, strategy, and grit. Yet he only won by four seconds over countryman Moses “The Big Engine” Mosop, one of history’s forgotten marathon comets.

In the past 5-6 years, the sport has fully integrated the era of “super shoes.” With their carbon-plated inserts and energy-returning midsole foam, these shoes have rewritten the rules of speed. Yet, despite this advanced technology, nobody has come along to better Mutai’s Boston mark, or even come close, despite it only being the 20th fastest time in marathon history as of April 14, 2025. The fastest we have seen since Mutai in Boston was Evans Chebet‘s 2:05:54 win in 2023.

Mutai’s mark, now standing for 12 years, equals Ndeti’s 1994 2:07:15 for the longest lasting record at Boston.

So, too, is it with Boston’s women’s record. Super shoes notwithstanding, and the other-worldly marathon record of 2:09:56 by Ruth Chepngetich in Chicago 2024, the women’s record on the Boston course remains ten minutes slower. And even that has asterisk.

Boston’s record, 2:19:59 from 2014 by Ethiopia’s Buzunesh Deba, was originally a second place performance. But officials later disqualified Kenya’s Rita Jeptoo and stripped her of her record after discovering she had taken performance-enhancing drugs.

Super shoes may promise faster times, easier training, and quicker recovery, but Boston’s challenges remain the same: the Newton hills still punish overzealous pacing, and unpredictable New England weather often conspires against record attempts.

Today, a new breed of athlete shapes the marathon world: young, altitude-born runners from East Africa and a new breed of Americans no longer fearful of their Kenyan and Ethiopian rivals, all come to Boston armed with super shoes and the science of modern training and hydration.

Yet Boston remains distinct among the world’s great marathons. With no pacesetters and its rolling course, the race still demands strategy, patience, and respect.

The siren call of its early downhills tempts runners to burn brightly and crash hard. But those who remain deaf to its song of speed and endure—the true competitors—find the balance between courage and control.

Boston, in the end, isn’t about speed alone. It’s about the mastery of the competition, the course, and oneself. It is a tricky calculus, but the rewards are worth the risk. And with moderate conditions predicted for Monday’s 129th edition, the sirens will sing again, for sure. Which young Ulysses will heed their call this year? Or will they all be savvy savants?

END